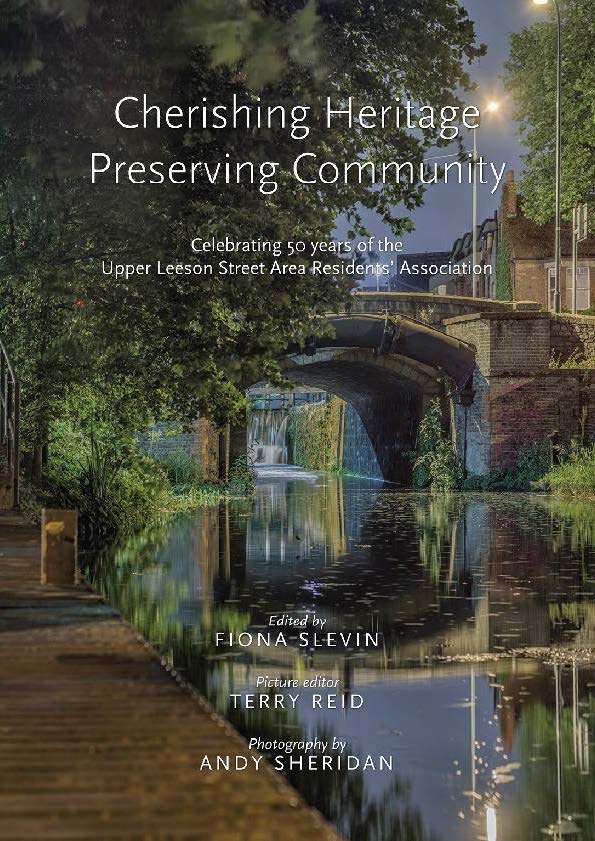

Our history

A historic year globally

The timing of Ulsara’s emergence in 1968 was very much tied to local issues of zoning and development and fears about the potential erosion of the residential character of a neighbourhood. The year, however, was a historic one by any measure. In the U.S., the civil rights movement gained ground, but the assassination of Martin Luther King on 4 April, and Robert Kennedy two months later, dazed the nation and the world. Richard Nixon became president. The war in Vietnam continued and resistance to it grew. Biafra seceded from Nigeria, resulting in a civil war and blockade that caused the death from starvation of almost two million Biafrans. In Czechoslovakia, the Prague Spring uprising was quashed within months by Soviet tanks. In Paris, students clashed with police and hundreds of thousands of workers joined a general strike. In the U.K., protestors took to the streets after Enoch Powell’s anti-immigrant, ‘rivers of blood’ speech. In Northern Ireland, the civil rights movement gained force as protesters demanded social reforms and ‘one man, one vote’. In Ireland, the Fianna Fáil government held a referendum to change the electoral system from proportional representation to a ‘first past the post’ system: it was rejected. At the Olympic games, U.S. medal winners, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, gave the Black Power salute on the podium as a protest against racism. Pope Paul VI issued the Humanae Vitae encyclical, declaring that artificial contraception was ‘in opposition to the plan of God’. On Christmas Eve, humans orbited the moon for the first time, when three astronauts aboard Apollo 8 circled the moon andsuccessfully returned to Earth.

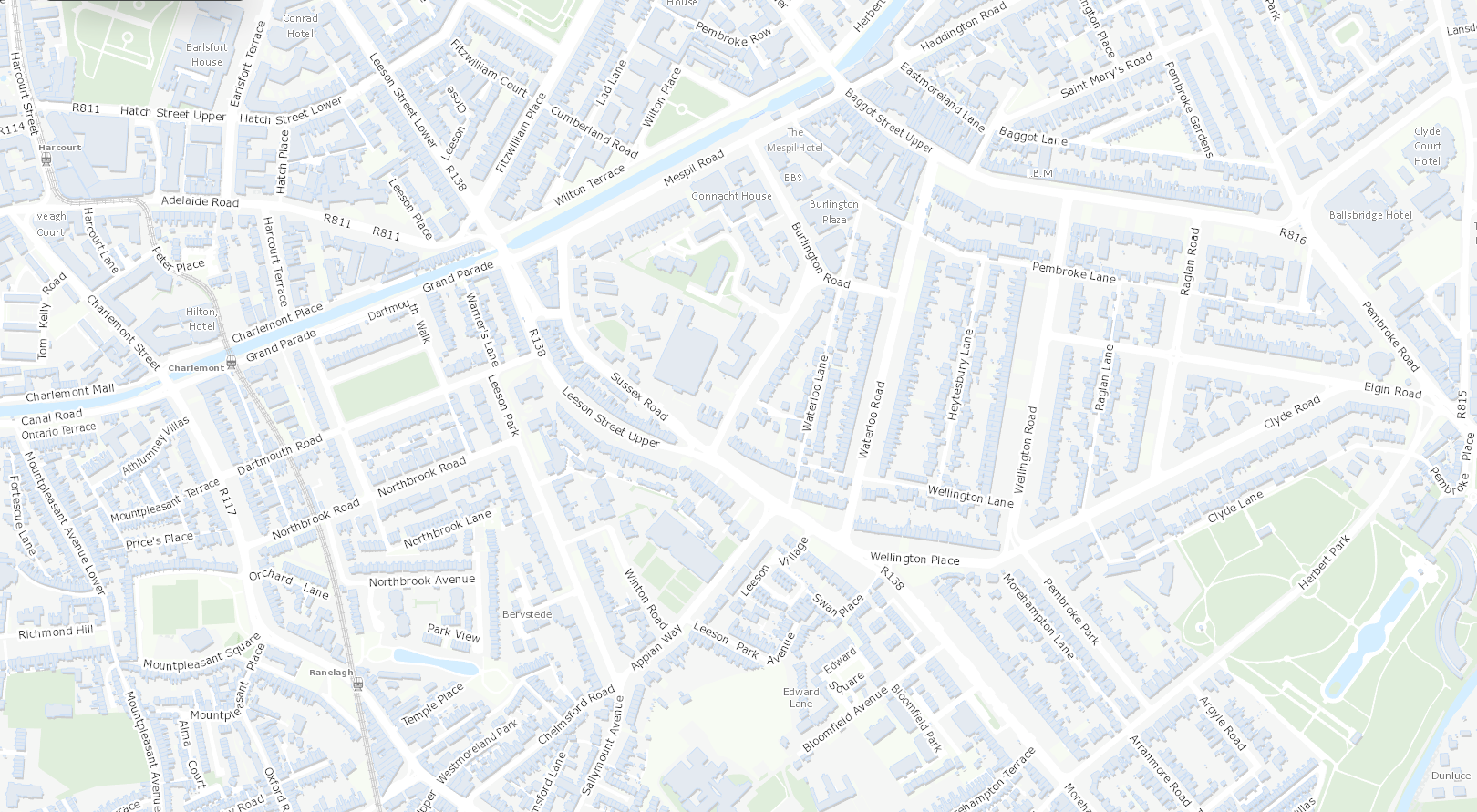

Resisting rezoning

In a global context the concerns of Dublin 4 residents were hardly a

matter of life and death, but they mirrored, in however small a way, the active resistance that was happening on many levels on a global scale. In any case, Carmencita Hederman’s letter to The Irish Times of 4 April 1968 galvanised a group of residents who came together to fight the rezoning proposal. They recognised that this mature, settled and architecturally cohesive neighbourhood would suffer considerable damage if the provisions in the plan were allowed to stand. The nascent association won the battle and succeeded in having the district rezoned for residential use only. And so it remains to this day. Rather than rest on that first success, the association continued and adopted the name Ulsara: Upper Leeson Street Area Residents’ Association. For the past 50 years, Ulsara has battled with developersover the interpretation and implementation of the Dublin Development Plan and subsequent Planning and Development Acts. Its tactics have been varied, informed and occasionally ingenious, ranging from formal planning and appeal representations, to court appearances, street protests, deft media management, lobbying and downright charm.

Sustaining core aims for 50 years

Much of the association’s early work was directed at preserving the distinctive architectural features of the area. This included fighting against the unauthorised removal of front garden railings and the creation of guidelines for the design of front gardens where off-street parking was permitted. Ulsara was also instrumental in seeking protected structure designation for the Georgian and Victorian buildings andterraces of this conservation area.

Over the years, the association has involved itself in a broad set of issues that, in their own way, had implications for the social and environmental landscape. It actively opposed the proposal to use the Grand Canal as a route for a motorway and the proposal to build an oil refinery in Dublin Bay. It also persuaded public utilities to be more sensitive in the location of installations, particularly telephone poles on the footpaths in the neighbourhood.

The association lobbied on the matter of fees demanded in the planning process. It liaised with neighbouring residents’ associations to present a united front or to increase its influence and scale. It was as proactive as it was reactive: the association was influential in the formation of a mews development

policy in Dublin Development Plans and in the provision of public parks at Ranelagh Gardens and Dartmouth Square. The residents of Dartmouth Square were the first in Dublin city to adopt a residential discparking scheme. The aims of Ulsara, as set out by the founders, have endured. They

remain ‘to promote the conservation and preservation of the residential character and amenities of the neighbourhood, including the maintenance of green spaces, as well as the distinctive Georgian and Victorian architectural features of this area of Dublin, and to encourage the development of community life in the area’.

It is easy to reduce the work of Ulsara to upper-middle class professionals using their power and money to maintain their privileged lifestyle and ensure unwanted development was concentrated outside of their backyard. But the Ulsara story has resonance and relevance beyond its aims and location. At a time when Dublin’s architectural heritage was under attack, Ulsara members stepped up and mobilised to protect our shared heritage. Their story shows how one individual can make a difference; how civic activism can succeed when it is resolute and sustained; and how clever campaigns apply a variety of talents and approaches. The Ulsara story is also a singular example of public engagement by a segment of society that is sometimes accused of being too disengaged and too silent about the issues of the day.